|

|

Post by TCTV on Dec 27, 2010 16:27:46 GMT -5

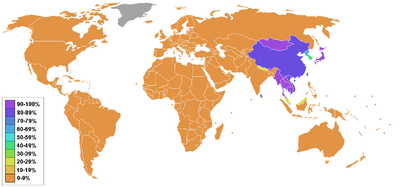

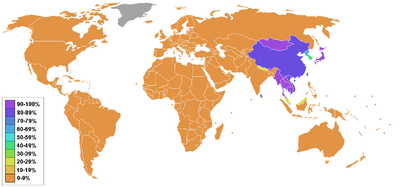

Buddhist meditationFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Buddhist Meditation) www.basicbuddhism.org/index.cfm?GPID=19www.buddhadhammasangha.com/SecondLevelSite/ThirdLevelSite/AudioAndVideo/Audio/BuddhistChanting.htmwww.watmetta.org/The Buddhist Temple of America, 5615 Howard Avenue, Ontario, CA 91762 USA.  Buddhist proselytism at the time of emperor Ashoka (260–218 BCE).  Dharma or Concepts Four Noble Truths Dependent Origination Impermanence Suffering · Middle Way Non-self · Emptiness Five Aggregates Karma · Rebirth Samsara · Cosmology Practices Three Jewels Precepts · Perfections Meditation · Wisdom Noble Eightfold Path Aids to Enlightenment Monasticism · Laity Nirvāṇa Four Stages · Arhat Buddha · Bodhisattva Traditions · Canons Theravāda · Pali Mahāyāna · Chinese Vajrayāna · Tibetan Countries and Regions Related topics Comparative studies Cultural elements Criticism v • d • e Buddhist meditation refers to the meditative practices associated with the religion and philosophy of Buddhism. Core meditation techniques have been preserved in ancient Buddhist texts and have proliferated and diversified through teacher-student transmissions. Buddhists pursue meditation as part of the path toward Enlightenment and Nirvana.[1] The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are bhāvanā[2] and jhāna/dhyāna.[3] Buddhist meditation techniques have become increasingly popular in the wider world, with many non-Buddhists taking them up for a variety of reasons. Given the large number and diversity of traditional Buddhist meditation practices, this article primarily identifies authoritative contextual frameworks – both contemporary and canonical – for the variety of practices. For those seeking school-specific meditation information, it may be more appropriate to simply view the articles listed in the "See also" section below. Contents [hide] 1 Key Terms 2 Meditation in Buddhist traditions 2.1 In early tradition 2.1.1 Types of meditation 2.1.2 Four foundations for mindfulness 2.1.3 Serenity and insight 2.1.4 From the Pali Commentaries 2.1.5 In Contemporary Theravāda 2.2 In Mahāyāna Buddhism 2.2.1 Meditation in the Pure Land school 2.2.1.1 Mindfulness of Amitābha Buddha 2.2.1.2 Pure Land Rebirth Dhāraṇī 2.2.1.3 Visualization methods 2.2.2 Meditation in the Chán/Zen school 2.2.2.1 Pointing to the nature of the mind 2.2.2.2 Contemplating meditation cases 2.2.3 Meditation in the Tiantai school 2.2.3.1 Tiantai śamatha-vipaśyanā 2.2.3.2 Esoteric practices in Japan 3 Adoption by non-Buddhists 4 See also 5 Notes 6 Bibliography 7 External links  [edit] Key TermsEnglish Pali Sanskrit Chinese Tibetan mindfulness sati smṛti 念 (niàn) trenpa (wylie: dran pa) awareness/clear comprehension sampajañña samprajaña 正知力 (zhèng zhī lì) sheshin (shes bzhin) vigilance/heedfulness appamada apramāda 不放逸座 (bù fàng yì zuò) bakyö (bag yod) ardency atappa ātapaḥ 勇猛 (yǒng měng) nyima (nyi ma) attention/engagement manasikara manaskāraḥ 如理作意 (rú lǐ zuò yì) yila jeypa (yid la byed pa) foundation of mindfulness satipaṭṭhāna smṛtyupasthāna 念住 (niànzhù) trenpa neybar zagpa (dran pa nye bar gzhag pa) mindfulness of breathing ānāpānasati ānāpānasmṛti 安那般那 (ānnàbānnà) wūk trenpa (dbugs dran pa) calm abiding/cessation samatha śamatha 止 (zhǐ) shiney (zhi gnas) insight/clear seeing/contemplation vipassanā vipaśyanā 観 (guān) lhakthong (lhag mthong) concentration/absorption samādhi samādhi 三昧 (sānmèi) tendzin (ting nge dzin) concentration/absorption jhāna dhyāna 禪 (chán) samten (bsam gtan) meditation/development/cultivation bhāvanā bhāvanā 修行 (xiūxíng) gompa (sgom pa) analytical/investigative meditation — *vicāra-bhāvanā — chegom (dpyad sgom) settling meditation — *sthāpya-bhāvanā — jokgom ('jog sgom) [edit] Meditation in Buddhist traditionsWhile there are some similar meditative practices — such as breath meditation and various recollections (anussati) — that are used across Buddhist schools, there is also significant diversity. In the Theravāda tradition alone, there are over fifty methods for developing mindfulness and forty for developing concentration, while in the Tibetan tradition there are thousands of visualization meditations.[4] Most classical and contemporary Buddhist meditation guides are school specific.[5] Only a few teachers attempt to synthesize, crystallize and categorize practices from multiple Buddhist traditions. [edit] In early traditionThe earliest tradition of Buddhist practice is preserved in the nikāya/āgamas, and is adhered to by the Theravāda lineage. It was also the focus of the other now-extinct early Buddhist schools, and has been incorporated to greater and lesser degrees into the Tibetan Buddhist tradition and many East Asian Mahāyāna traditions. [edit] Types of meditationMeditation on the Buddhist Path Most Buddhist traditions recognize that the path to Enlightenment entails three types of training: virtue (sīla); meditation (samadhi); and, wisdom (paññā).[6] Thus, meditative prowess alone is not sufficient; it is but one part of the path. In other words, in Buddhism, in tandem with mental cultivation, ethical development and wise understanding are also necessary for the attainment of the highest goal.[7] In terms of early traditions as found in the vast Pali canon and the Āgamas, meditation can be contextualized as part of the Noble Eightfold Path, explicitly in regard to: Right Mindfulness (samma sati) – exemplified by the Buddha's Four Foundations of Mindfulness (see Satipatthana Sutta). Right Concentration (samma samadhi) – culminating in jhanic absorptions through the meditative development of samatha.[8] And implicitly in regard to : Right View (samma ditthi) – embodying wisdom traditionally attained through the meditative development of vipassana founded on samatha.[9] Classic texts in the Pali literature enumerating meditative subjects include the Satipatthana Sutta (MN 10) and the Visuddhimagga's Part II, "Concentration" (Samadhi). [edit] Four foundations for mindfulnessMain article: Satipatthana Sutta Lord Buddha meditatingIn the Satipatthana Sutta, the Buddha identifies four foundations for mindfulness: the body, feelings, mind states and mental objects. He further enumerates the following objects as bases for the meditative development of mindfulness: Body (kāyā): Breathing (see Anapanasati Sutta), Postures, Clear Comprehending, Reflections on Repulsiveness of the Body, Reflections on Material Elements, Cemetery Contemplations Feelings (vedanā), whether pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral Mind (cittā) Mental Contents (dhammā): Hindrances, Aggregates, Sense-Bases, Factors of Enlightenment, and the Four Noble Truths. Meditation on these subjects develops insight.[10] [edit] Serenity and insightThe Buddha is said to have identified two paramount mental qualities that arise from wholesome meditative practice: "serenity" or "tranquillity" (Pali: samatha) which steadies, composes, unifies and concentrates the mind; "insight" (Pali: vipassana) which enables one to see, explore and discern "formations" (conditioned phenomena based on the five aggregates).[11] Through the meditative development of serenity, one is able to suppress obscuring hindrances; and, with the suppression of the hindrances, it is through the meditative development of insight that one gains liberating wisdom.[12] Moreover, the Buddha is said to have extolled serenity and insight as conduits for attaining Nibbana (Pali; Skt.: Nirvana), the unconditioned state as in the "Kimsuka Tree Sutta" (SN 35.245), where the Buddha provides an elaborate metaphor in which serenity and insight are "the swift pair of messengers" who deliver the message of Nibbana via the Noble Eightfold Path.[13] In the "Four Ways to Arahantship Sutta" (AN 4.170), Ven. Ananda reports that people attain arahantship using serenity and insight in one of three ways: 1.they develop serenity and then insight (Pali: samatha-pubbangamam vipassanam) 2.they develop insight and then serenity (Pali: vipassana-pubbangamam samatham)[14] 3.they develop serenity and insight in tandem (Pali: samatha-vipassanam yuganaddham) as in, for instance, obtaining the first jhana, and then seeing in the associated aggregates the three marks of existence, before proceeding to the second jhana.[15] In the Pali canon, the Buddha never mentions independent samatha and vipassana meditation practices; instead, samatha and vipassana are two qualities of mind to be developed through meditation.[16] Nonetheless, some meditation practices (such as contemplation of a kasina object) favor the development of samatha, others are conducive to the development of vipassana (such as contemplation of the aggregates), while others (such as mindfulness of breathing) are classically used for developing both mental qualities.[17] [edit] From the Pali CommentariesMain article: Kammatthana Buddhaghosa's forty meditation subjects are described in the Visuddhimagga. Almost all of these are described in the early texts.[18] Buddhaghosa advises that, for the purpose of developing concentration and "consciousness," a person should "apprehend from among the forty meditation subjects one that suits his own temperament" with the advice of a "good friend" (kalyana mitta) who is knowledgeable in the different meditation subjects (Ch. III, § 28).[19] Buddhaghosa subsequently elaborates on the forty meditation subjects as follows (Ch. III, §104; Chs. IV - XI):[20] ten kasinas: earth, water, fire, air, blue, yellow, red, white, light, and "limited-space". ten kinds of foulness: "the bloated, the livid, the festering, the cut-up, the gnawed, the scattered, the hacked and scattered, the bleeding, the worm-infested, and a skeleton". ten recollections: the Buddha, the Dhamma, the Sangha, virtue, generosity, the virtues of deities, death (see Upajjhatthana Sutta), the body, the breath (see anapanasati), and peace (see Nibbana). four divine abodes: metta, karuṇā, mudita, and upekkha. four immaterial states: boundless space, boundless perception, nothingness, and neither perception nor non-perception. one perception (of "repulsiveness in nutriment") one "defining" (that is, the four elements) When one overlays Buddhaghosa's 40 meditative subjects for the development of concentration with the Buddha's foundations of mindfulness, three practices are found to be in common: breath meditation, foulness meditation (which is similar to the Sattipatthana Sutta's cemetery contemplations, and to contemplation of bodily repulsiveness), and contemplation of the four elements. According to Pali commentaries, breath meditation can lead one to the equanimous fourth jhanic absorption. Contemplation of foulness can lead to the attainment of the first jhana, and contemplation of the four elements culminates in pre-jhana access concentration.[21] [edit] In Contemporary TheravādaParticularly influential from the twentieth century onward has been the "New Burmese Method" or "Vipassana School" approach to samatha and vipassana developed by Mingun Jetavana Sayādaw U Nārada and popularized by Mahasi Sayadaw. Here samatha is considered an optional but not necessary component of the practice—vipassana is possible without it. Another Burmese method, derived from Ledi Sayadaw via U Ba Khin and S. N. Goenka, takes a similar approach. Other Burmese traditions popularized in the west, notably that of Pa Auk Sayadaw, uphold the emphasis on samatha explicit in the commentarial tradition of the Visuddhimagga. Also influential is the Thai Forest tradition deriving from Ajahn Mun and popularized by Ajahn Chah, which, in contrast, stresses the inseparability of the two practices, and the essential necessity of both practices. Other noted practitioners in this tradition include Ajahn Thate and Ajahn Maha Bua, among others.[22] [edit] In Mahāyāna BuddhismMahāyāna Buddhism includes numerous schools of practice, which each draw upon various Buddhist sūtras, philosophical treatises, and commentaries. Accordingly, each school has its own meditation methods for the purpose of developing samādhi and prajñā, with the goal of ultimately attaining enlightenment. Nevertheless, each has its own emphasis, mode of expression, and philosophical outlook. In his classic book on meditation of the various Chinese Buddhist traditions, Charles Luk writes, "The Buddha Dharma is useless if it is not put into actual practice, because if we do not have personal experience of it, it will be alien to us and we will never awaken to it in spite of our book learning."[23] Venerable Nan Huaijin echoes similar sentiments about the importance of meditation by remarking, "Intellectual reasoning is just another spinning of the sixth consciousness, whereas the practice of meditation is the true entry into the Dharma."[24] [edit] Meditation in the Pure Land school[edit] Mindfulness of Amitābha BuddhaIn the Pure Land tradition of Buddhism, repeating the name of Amitābha Buddha is traditionally a form of Mindfulness of the Buddha (Skt. buddhānusmṛti). This term was translated into Chinese as nianfo (念佛), by which it is popularly known in English. The practice is described as calling the buddha to mind by repeating his name, to enable the practitioner to bring all his or her attention upon that buddha (samādhi).[25] This may be done vocally or mentally, and with or without the use of Buddhist prayer beads. Those who practice this method often commit to a fixed set of repetitions per day, often from 50,000 to over 500,000.[26] According to tradition, the second patriarch of the Pure Land school, Shandao, is said to have practiced this day and night without interruption, each time emitting light from his mouth. Therefore he was bestowed with the title "Great Master of Light" (大師光明) by the Tang Dynasty emperor Gao Zong (高宗).[27] In addition, in Chinese Buddhism there is a related practice called the "dual path of Chán and Pure Land cultivation", which is also called the "dual path of emptiness and existence."[28] As taught by Venerable Nan Huaijin, the name of Amitābha Buddha is recited slowly, and the mind is emptied out after each repetition. When idle thoughts arise, the phrase is repeated again to clear them. With constant practice, the mind is able to remain peacefully in emptiness, culminating in the attainment of samādhi.[29] [edit] Pure Land Rebirth DhāraṇīRepeating the Pure Land Rebirth Dhāraṇī is another method in Pure Land Buddhism. Similar to the mindfulness practice of repeating the name of Amitābha Buddha, this dhāraṇī is another method of meditation and recitation in Pure Land Buddhism. The repetition of this dhāraṇī is said to be very popular among traditional Chinese Buddhists.[30] It is traditionally preserved in Sanskrit, and it is said that when a devotee succeeds in realizing singleness of mind by repeating a mantra, its true and profound meaning will be clearly revealed.[31] namo amitābhāya tathāgatāya tadyathā amṛtabhave amṛtasaṃbhave amṛtavikrānte amṛtavikrāntagāmini gagana kīrtīchare svāhā [edit] Visualization methodsAnother practise found in Pure Land Buddhism is meditative contemplation and visualization of Amitābha Buddha, his attendant bodhisattvas, and the Pure Land. The basis of this is found in the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra ("Amitābha Meditation Sūtra"), in which the Buddha describes to Queen Vaidehi the practices of thirteen progressive visualization methods, corresponding to the attainment of various levels of rebirth in the Pure Land.[32] Visualization practises for Amitābha are popular among esoteric Buddhist sects, such as Japanese Shingon Buddhism. [edit] Meditation in the Chán/Zen school[edit] Pointing to the nature of the mindIn the earliest traditions of Chán/Zen Buddhism, it is said that there was no formal method of meditation. Instead, the teacher would use various didactic methods to point to the true nature of the mind, also known as Buddha-nature. This method is referred to as the "Mind Dharma", and exemplified in the story of Śākyamuni Buddha holding up a flower silently, and Mahākāśyapa smiling as he understood.[33] A traditional formula of this is, "Chán points directly to the human mind, to enable people to see their true nature and become buddhas."[34] In the early era of the Chán school, there was no fixed method or simple formula for teaching meditation, and all instructions were simply heuristic methods; therefore the Chán school was called the "Gateless Gate."[35] [edit] Contemplating meditation casesIt is said traditionally that when the minds of people in society became more complicated and when they could not make progress so easily, the masters of the Chán school were forced to change their methods.[36] These involved particular words and phrases, shouts, roars of laughter, sighs, gestures, or blows from a staff. These were all meant to awaken the student to the essential truth of the mind, and were later called gōng'àn (公案), or kōan in Japanese.[37] These didactic phrases and methods were to be contemplated, and example of such a device is a phrase that turns around the practice of mindfulness: "Who is being mindful of the Buddha?"[38] The teachers all instructed their students to give rise to a gentle feeling of doubt at all times while practicing, so as to strip the mind of seeing, hearing, feeling, and knowing, and ensure its constant rest and undisturbed condition.[39] Charles Luk explains the essential function of contemplating such a meditation case with doubt:[40] Since the student cannot stop all his thoughts at one stroke, he is taught to use this poison-against-poison device to realize singleness of thought, which is fundamentally wrong but will disappear when it falls into disuse, and gives way to singleness of mind, which is a precondition of the realization of the self-mind for the perception of self-nature and attainment of Bodhi. [edit] Meditation in the Tiantai school[edit] Tiantai śamatha-vipaśyanāIn China it has been traditionally held that the meditation methods used by the Tiantai school are the most systematic and comprehensive of all.[41] In addition to its doctrinal basis in Indian Buddhist texts, the Tiantai school also emphasizes use of its own meditation texts which emphasize the principles of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Of these texts, Zhiyi's Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā (小止観), Mahā-śamatha-vipaśyanā (摩訶止観), and Six Subtle Dharma Gates (六妙法門) are the most widely read in China.[42] Rujun Wu (1993: p. 1) identifies the work Mahā-śamatha-vipaśyanā of Zhiyi as the seminal meditation text of the Tiantai school.[43] Regarding the functions of śamatha and vipaśyanā in meditation, Zhiyi writes in his work Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā:[44] The attainment of Nirvāṇa is realizable by many methods whose essentials do not go beyond the practice of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Śamatha is the first step to untie all bonds and vipaśyanā is essential to root out delusion. Śamatha provides nourishment for the preservation of the knowing mind, and vipaśyanā is the skillful art of promoting spiritual understanding. Śamatha is the unsurpassed cause of samādhi, while vipaśyanā begets wisdom. The Tiantai school also places a great emphasis on ānāpānasmṛti, or mindfulness of breathing, in accordance with the principles of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Zhiyi classifies breathing into four main categories: panting (喘), unhurried breathing (風), deep and quiet breathing (氣), and stillness or rest (息). Zhiyi holds that the first three kinds of breathing are incorrect, while the fourth is correct, and that the breathing should reach stillness and rest.[45] [edit] Esoteric practices in JapanOne of the adaptations by the Japanese Tendai (Ch. Tiantai) school was the introduction of esoteric practices (Mikkyo) into Tendai Buddhism, which was later named Taimitsu by Ennin. Eventually, according to Tendai Taimitsu doctrine, the esoteric rituals came to be considered of equal importance with the exoteric teachings of the Lotus Sutra. Therefore, by chanting mantras, maintaining mudras, or performing certain meditations, one is able to see that the sense experiences are the teachings of Buddha, have faith that one is inherently an enlightened being, and one can attain enlightenment within this very body. The origins of Taimitsu are found in China, similar to the lineage that Kukai encountered in his visit to China during the Tang Dynasty, and Saicho's disciples were encouraged to study under Kukai.[46]

|

|

|

|

Post by TCTV on Dec 27, 2010 16:28:37 GMT -5

Adoption by non-BuddhistsMain article: Mindfulness (psychology) For a long time people have practiced meditation, based on Buddhist meditation principles, in order to effect mundane and worldly benefit.[47] Buddhist meditation techniques are increasingly being employed by psychologists and psychiatrists to help alleviate a variety of health conditions such as anxiety and depression.[48] As such, mindfulness and other Buddhist meditation techniques are being advocated in the West by innovative psychologists and expert Buddhist meditation teachers such as Clive Sherlock, Mother Sayamagyi, S.N. Goenka, Jon Kabat-Zinn, Jack Kornfield, Joseph Goldstein, Tara Brach, Alan Clements, and Sharon Salzberg, who have been widely attributed with playing a significant role in integrating the healing aspects of Buddhist meditation practices with the concept of psychological awareness and healing. The accounts of meditative states in the Buddhist texts are in some regards free of dogma, so much so that the Buddhist scheme has been adopted by Western psychologists attempting to describe the phenomenon of meditation in general.[49] Nevertheless, it is exceedingly common to encounter the Buddha describing meditative states involving the attainment of such magical powers (P. iddhi) as the ability to multiply one's body into many and into one again, appear and vanish at will, pass through solid objects as if space, rise and sink in the ground as if in water, walking on water as if land, fly through the skies, touching anything at any distance (even the moon or sun), and travel to other worlds (like the world of Brahma) with or without the body, among other things.[50][51][52] [edit] See alsoTheravada Buddhist meditation practices: Anapanasati - focusing on the breath Metta - cultivation of compassion and loving-kindness Kammaṭṭhāna Samatha - calm abiding Vipassana - insight Mahasati Meditation Zen Buddhist meditation practices: Shikantaza - just sitting Zazen Koan Vajrayana and Tibetan Buddhism meditation practices: Tantra techniques Ngondro - preliminary practices Tonglen - giving and receiving Phowa - transference of consciousness at the time of death Chöd - cutting through fear by confronting it Mahamudra - the Kagyu version of 'entering the all-pervading Dharmadatu', the 'nondual state', or the 'absorption state' Dzogchen - the natural state, the Nyingma version of Mahamudra The Four Immeasurables, Metta Tantra Related Buddhist practices: Mindfulness - awareness in the present moment Mindfulness (psychology) - Western applications of Buddhist ideas Satipatthana chanting and mantra Proper floor-sitting postures and supports while meditating: Floor sitting: cross-legged (full lotus, half lotus, Burmese) or seiza Cushions: zafu, zabuton Traditional Buddhist texts on meditation: Anapanasati Sutta Satipatthana Sutta Visuddhimagga Traditional preliminary practices to Buddhist meditation: prostrations (also see Ngondro) refuge in the Triple Gem Five Precepts Analog in Vedas: Paramatma Ksirodakasayi Vishnu [edit] Notes1.^ For instance, Kamalashila (2003), p. 4, states that Buddhist meditation "includes any method of meditation that has Enlightenment as its ultimate aim." Likewise, Bodhi (1999) writes: "To arrive at the experiential realization of the truths it is necessary to take up the practice of meditation.... At the climax of such contemplation the mental eye ... shifts its focus to the unconditioned state, Nibbana...." A similar although in some ways slightly broader definition is provided by Fischer-Schreiber et al. (1991), p. 142: "Meditation – general term for a multitude of religious practices, often quite different in method, but all having the same goal: to bring the consciousness of the practitioner to a state in which he can come to an experience of 'awakening,' 'liberation,' 'enlightenment.'" Kamalashila (2003) further allows that some Buddhist meditations are "of a more preparatory nature" (p. 4). 2.^ The Pāli and Sanskrit word bhāvanā literally means "development" as in "mental development." For the association of this term with "meditation," see Epstein (1995), p. 105; and, Fischer-Schreiber et al. (1991), p. 20. As an example from a well-known discourse of the Pali Canon, in "The Greater Exhortation to Rahula" (Maha-Rahulovada Sutta, MN 62), Ven. Sariputta tells Ven. Rahula (in Pali, based on VRI, n.d.): ānāpānassatiṃ, rāhula, bhāvanaṃ bhāvehi. Thanissaro (2006) translates this as: "Rahula, develop the meditation [bhāvana] of mindfulness of in-&-out breathing." (Square-bracketed Pali word included based on Thanissaro, 2006, end note.) 3.^ See, for example, Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), entry for "jhāna1"; Thanissaro (1997); as well as, Kapleau (1989), p. 385, for the derivation of the word "zen" from Sanskrit "dhyāna." PTS Secretary Dr. Rupert Gethin, in describing the activities of wandering ascetics contemporaneous with the Buddha, wrote: "...[T]here is the cultivation of meditative and contemplative techniques aimed at producing what might, for the lack of a suitable technical term in English, be referred to as 'altered states of consciousness'. In the technical vocabulary of Indian religious texts such states come to be termed 'meditations' ([Skt.:] dhyāna / [Pali:] jhāna) or 'concentrations' (samādhi); the attainment of such states of consciousness was generally regarded as bringing the practitioner to deeper knowledge and experience of the nature of the world." (Gethin, 1998, p. 10.) 4.^ Goldstein (2003) writes that, in regard to the Satipatthana Sutta, "there are more than fifty different practices outlined in this Sutta. The meditations that derive from these foundations of mindfulness are called vipassana..., and in one form or another — and by whatever name — are found in all the major Buddhist traditions" (p. 92). The forty concentrative meditation subjects refer to Visuddhimagga's oft-referenced enumeration. Regarding Tibetan visualizations, Kamalashila (2003), writes: "The Tara meditation ... is one example out of thousands of subjects for visualization meditation, each one arising out of some meditator's visionary experience of enlightened qualities, seen in the form of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas" (p. 227). 5.^ Examples of contemporary school-specific "classics" include, from the Theravada tradition, Nyanaponika (1996) and, from the Zen tradition, Kapleau (1989). 6.^ For instance, from the Pali Canon, see MN 44 (Thanissaro, 1998a) and AN 3:88 (Thanissaro, 1998b). In Mahayana tradition, the Lotus Sutra lists the Six Perfections (paramita) which echoes the threefold training with the inclusion of virtue (śīla), concentration (samadhi) and wisdom (prajñā). 7.^ Dharmacarini Manishini, Western Buddhist Review. Accessed at www.westernbuddhistreview.com/vol4/kamma_in_context.html8.^ See, for instance, Bodhi (1999). 9.^ For example, Bodhi (1999), in discussing a latter stage of developing Right View (that of "penetrating" the Four Noble Truths), states: To arrive at the experiential realization of the truths it is necessary to take up the practice of meditation — first to strengthen the capacity for sustained concentration, then to develop insight. 10.^ For instance, see Solé-Leris (1986), p. 75; and, Goldstein (2003), p. 92. 11.^ These definitions of samatha and vipassana are based on the "Four Kinds of Persons Sutta" (AN 4.94). This article's text is primarily based on Bodhi (2005), pp. 269-70, 440 n. 13. See also Thanissaro (1998d). 12.^ See, for instance, AN 2.30 in Bodhi (2005), pp. 267-68, and Thanissaro (1998e). 13.^ Bodhi (2000), pp. 1251-53. See also Thanissaro (1998c) (where this sutta is identified as SN 35.204). See also, for instance, a discourse (Pali: sutta) entitled, "Serenity and Insight" (SN 43.2), where the Buddha states: "And what, bhikkhus, is the path leading to the unconditioned? Serenity and insight...." (Bodhi, 2000, pp. 1372-73). 14.^ While the Nikayas identify that the pursuit of vipassana can precede the pursuit of samatha, a fruitful vipassana-oriented practice must still be based upon the achievement of stabilizing "access concentration" (Pali: upacara samadhi). 15.^ Bodhi (2005), pp. 268, 439 nn. 7, 9, 10. See also Thanissaro (1998f). 16.^ See Thanissaro (1997) where for instance he underlines: When [the Pali discourses] depict the Buddha telling his disciples to go meditate, they never quote him as saying 'go do vipassana,' but always 'go do jhana.' And they never equate the word vipassana with any mindfulness techniques. In the few instances where they do mention vipassana, they almost always pair it with samatha — not as two alternative methods, but as two qualities of mind that a person may 'gain' or 'be endowed with,' and that should be developed together. Similarly, referencing MN 151, vv. 13-19, and AN IV, 125-27, Ajahn Brahm (who, like Bhikkhu Thanissaro, is of the Thai Forest Tradition) writes: Some traditions speak of two types of meditation, insight meditation (vipassana) and calm meditation (samatha). In fact, the two are indivisible facets of the same process. Calm is the peaceful happiness born of meditation; insight is the clear understanding born of the same meditation. Calm leads to insight and insight leads to calm. (Brahm, 2006, p. 25.) 17.^ See, for instance, Bodhi (1999) and Nyanaponika (1996), p. 108. 18.^ Sarah Shaw, Buddhist meditation: an anthology of texts from the Pāli canon. Routledge, 2006, pages 6-8. A Jataka tale gives a list of 38 of them. [1]. 19.^ Buddhaghosa & Nanamoli (1999), pp. 85, 90. 20.^ Buddhaghosa & Nanamoli (1999), p. 110. 21.^ Regarding the jhanic attainments that are possible with different meditation techniques, see Gunaratana (1988). 22.^ Tiyavanich K. Forest Recollections: Wandering Monks in Twentieth-Century Thailand. University of Hawaii Press, 1997. 23.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 11 24.^ Nan, Huai-Chin. To Realize Enlightenment: Practice of the Cultivation Path. 1994. p. 1 25.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 83 26.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 83 27.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 84 28.^ Yuan, Margaret. Grass Mountain: A Seven Day Intensive in Ch'an Training with Master Nan Huai-Chin. 1986. p. 55 29.^ Yuan, Margaret. Grass Mountain: A Seven Day Intensive in Ch'an Training with Master Nan Huai-Chin. 1986. p. 55 30.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 84 31.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 84 32.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 85 33.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 44 34.^ Nan, Huai-Chin. Basic Buddhism: Exploring Buddhism and Zen. 1997. p. 92 35.^ Yuan, Margaret. Grass Mountain: A Seven Day Intensive in Ch'an Training with Master Nan Huai-Chin. 1986. p. 2 36.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 45 37.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 45 38.^ Hsuan Hua. The Chan Handbook. 2004. p. 47 39.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 49 40.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 48 41.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 110 42.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 110 43.^ Rujun Wu (1993). T'ien-T'ai Buddhism and early Mādhyamika. National Foreign Language Center Technical Reports. Buddhist studies program. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1561-0, 9780824815615. Source: [2] (accessed: Thursday April 22, 2010) 44.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 111 45.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 125 46.^ Abe, Ryuichi (1999). The Weaving of Mantra: Kukai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press. pp. 45. ISBN 0231112866. 47.^ See, for instance, Zongmi's description of bonpu and gedō zen, described further below. 48.^ Cornfield, J. (2003). Publisher's Weekly review of Radical acceptance: embracing your life with the heart of a Buddha [Editorial Review]. Retrieved April 17, 2009, from www.amazon.com/gp/product/0553801678/ ref=dp_proddesc_1?ie=UTF8&n=283155 49.^ Michael Carrithers, The Buddha, 1983, pages 33-34. Found in Founders of Faith, Oxford University Press, 1986. The author is referring to Pali literature. See however B. Alan Wallace, The bridge of quiescence: experiencing Tibetan Buddhist meditation. Carus Publishing Company, 1998, where the author demonstrates similar approaches to analyzing meditation within the Indo-Tibetan and Theravada traditions. 50.^ Iddhipada-vibhanga Sutta 51.^ Samaññaphala Sutta 52.^ Kevatta Sutta [edit] BibliographyBodhi, Bhikkhu (1999). The Noble Eightfold Path: The Way to the End of Suffering. Available on-line at www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/bodhi/waytoend.html. Bodhi, Bhikkhu (trans.) (2000). The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-331-1. Bodhi, Bhikkhu (ed.) (2005). In the Buddha's Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pāli Canon. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-491-1. Brach, Tara (ed.) (2003) Radical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life With the Heart of a Buddha. New York, Bantam Publications. ISBN 0-553-38099-0 Brahm, Ajahn (2006). Mindfulness, Bliss, and Beyond: A Meditator's Handbook. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-275-7. Buddhaghosa, Bhadantacariya & Bhikkhu Nanamoli (trans.) (1999), The Path of Purification: Visuddhimagga. Seattle: BPS Pariyatti Editions. ISBN 1-928706-00-2. Epstein, Mark (1995). Thoughts Without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective. BasicBooks. ISBN 0-465-03931-6 (cloth). ISBN 0-465-08585-7 (paper). Fischer-Schreiber, Ingrid, Franz-Karl Ehrhard, Michael S. Diener & Michael H. Kohn (trans.) (1991). The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen. Boston: Shambhala. ISBN 0-87773-520-4 (French ed.: Monique Thiollet (trans.) (1989). Dictionnaire de la Sagesse Orientale. Paris: Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-05611-6.) Gethin, Rupert (1998). The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-289223-1. Goldstein, Joseph (2003). One Dharma: The Emerging Western Buddhism. NY: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-251701-5. Hart, William (1987). The Art of Living: Vipassana Meditation: As Taught by S.N. Goenka. HarperOne. ISBN 0-06-063724-2 Gunaratana, Henepola (1988). The Jhanas in Theravada Buddhist Meditation (Wheel No. 351/353). Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 955-24-0035-X. Retrieved 2008-07-21 from "Access to Insight" at www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/gunaratana/wheel351.html. Kabat-Zinn, Jon (2001). Full Catastrophe Living. NY: Dell Publishing. ISBN 0-385-30312-2. Kamalashila (1996, 2003). Meditation: The Buddhist Art of Tranquility and Insight. Birmingham: Windhorse Publications. ISBN 1-899579-05-2. Available on-line at kamalashila.co.uk/Meditation_Web/index.htm. Kapleau, Phillip (1989). The Three Pillars of Zen: Teaching, Practice and Enlightenment. NY: Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-26093-8. Linehan, Marsha (1993). Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. NY: Guilford Press. ISBN 0-89862-183-6. Mipham, Sakyong (2003). Turning the Mind into an Ally. NY: Riverhead Books. ISBN 1-57322-206-2. Nyanaponika Thera (1996). The Heart of Buddhist Meditation. York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, Inc. ISBN 0-87728-073-8. Olendzki, Andrew (trans.) (2005). Sedaka Sutta: The Bamboo Acrobat (SN 47.19). Available at www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn47/sn47.019.olen.html. Rhys Davids, T.W. & William Stede (eds.) (1921-5). The Pali Text Society’s Pali–English Dictionary. Chipstead: Pali Text Society. A general on-line search engine for the PED is available at dsal.uchicago.edu/dictionaries/pali/. Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, ISBN 0-06-250834-2 Solé-Leris, Amadeo (1986). Tranquillity & Insight: An Introduction to the Oldest Form of Buddhist Meditation. Boston: Shambhala. ISBN 0-87773-385-6. Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997). One Tool Among Many: The Place of Vipassana in Buddhist Practice. Available on-line at www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/thanissaro/onetool.html. Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998a). Culavedalla Sutta: The Shorter Set of Questions-and-Answers (MN 44). Retrieved 2007-06-22 from "Access to Insight" at www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.044.than.html. Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998b). Sikkha Sutta: Trainings (1) (AN 3:38). Retrieved 2007-06-22 from "Access to Insight" at www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an03/an03.088.than.html. Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998c). Kimsuka Sutta: The Riddle Tree (SN 35.204). Available on-line at www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn35/sn35.204.than.html. Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998d). Samadhi Sutta: Concentration (Tranquillity and Insight) (AN 4.94). Available on-line at www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an04/an04.094.than.html. Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998e). Vijja-bhagiya Sutta: A Share in Clear Knowing (AN 2.30). Available on-line at www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an02/an02.030.than.html. Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998f). Yuganaddha Sutta: In Tandem (AN 4.170). Available on-line at www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an04/an04.170.than.html. Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (2006). Maha-Rahulovada Sutta: The Greater Exhortation to Rahula (MN 62). Retrieved 2007-11-07 from "Access to Insight" at www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.062.than.html. Vipassana Research Institute (VRI) (n.d.). Bhikkhuvaggo (second chapter of the second volume of the Majjhima Nikaya). Retrieved 2007-11-07 from VRI at www.tipitaka.org/romn/cscd/s0202m.mul1.xml. [edit] External links This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive and inappropriate external links. (December 2009) Buddhist Meditation Self-guided Basic Vajrayana Meditation Buddhist Meditation in the Theravada tradition Guided Meditations on the Lamrim — The Gradual Path to Enlightenment by Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron (PDF file). A guided Buddhist meditation by Thanissaro Bhikkhu Buddhanet - Buddhist Meditation E-Books Dhammakaya Meditation 40 Types of Buddhist Meditation - Who should use which? The Essence of Buddhist Meditation - Dhamma quotes & guides in attaining inner peace & release Shambhala Sun Magazine Buddhism. Culture. Meditation. Life. Saddhamma Foundation Information about practicing Buddhist meditation |

|

|

|

Post by TCTV on Dec 27, 2010 16:43:49 GMT -5

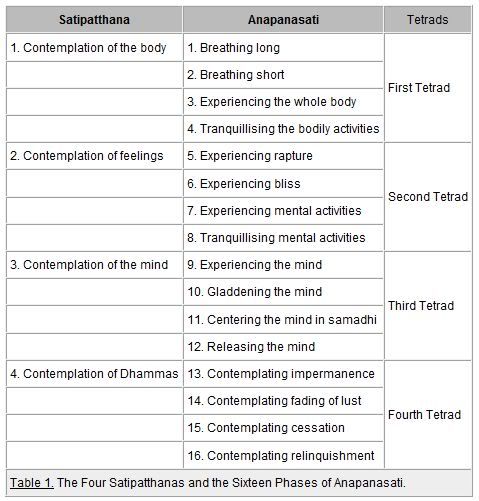

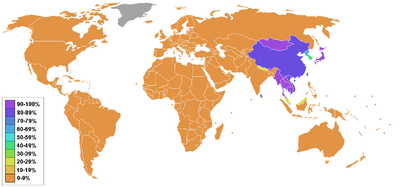

Anapanasati Quan Hoi Tho Ānāpānasati (Pali; Sanskrit: ānāpānasmṛti; Chinese: 安那般那; Pīnyīn: ānnàbānnà), meaning 'mindfulness of breathing' ("sati" means mindfulness; "ānāpāna" refers to inhalation and exhalation), is a fundamental form of meditation originally taught by the Buddha. Anapansati was originally taught by The Buddha in several sutras including the Ānāpānasati Sutta,[1] According to the Anapanasati Sutta and several teachers in Theravada Buddhism, anapanasati alone will lead to the removal of all one's defilements (kilesa) and eventually to Enlightenment. In the Tibetan Buddhist lineage, anapanasati is done to calm the mind in order to prepare one for the practices of Mahamudra and Dzogchen. Anapanasati can also be practised with other traditional meditation subjects including the four frames of reference[2] and mettā bhāvanā,[3] as is done in the Theravada lineage of modern Buddhism. Origins in BuddhismPart of a series on Buddhism Outline · Portal History Timeline · Councils Gautama Buddha Disciples Later Buddhists Dharma or Concepts Four Noble Truths Dependent Origination Impermanence Suffering · Middle Way Non-self · Emptiness Five Aggregates Karma · Rebirth Samsara · Cosmology Practices Three Jewels Precepts · Perfections Meditation · Wisdom Noble Eightfold Path Aids to Enlightenment Monasticism · Laity Nirvāṇa Four Stages · Arhat Buddha · Bodhisattva Traditions · Canons Theravāda · Pali Mahāyāna · Chinese Vajrayāna · Tibetan Countries and Regions Related topics Comparative studies Cultural elements Criticism v • d • e Anapanasati is a core meditation practice in Theravada, Tiantai, and Chán/Zen traditions of Buddhism, as well as a part of many modern Western mindfulness-based programs. In both ancient and modern times, anapanasati by itself is likely the most widely used Buddhist method for contemplating bodily phenomena.[4] The Anapanasati Sutta specifically concerns mindfulness of inhalation and exhalation, as a part of paying attention to one's body in quietude, and recommends the practice of ānāpānasati meditation as a means of cultivating the seven factors of awakening: sati (mindfulness), dhamma vicaya (analysis), viriya (persistence), which leads to piti (rapture), then to passaddhi (serenity), which in turn leads to samadhi (concentration) and then to upekkhā (equanimity). Finally, the Buddha taught that, with these factors developed in this progression, the practice of ānāpānasati would lead to release (Pali: nibbāna; Sanskrit: nirvana) from suffering (dukkha). Traditionally, anapanasati has been used as a basis for developing meditative concentration (samadhi) until reaching the state and practice of full absorption (jhana). It is the same state reached by the Buddha during his quest for Enlightenment.[5][clarification needed] [edit] The practice[edit] Traditional sourcesSee also: Anapanasati Sutta A traditional method given by The Buddha in the Satipatthana Sutta is to go into the forest and sit beneath a tree and then to simply watch the breath, if the breath is long, to notice that the breath is long, if the breath is short, to notice that the breath is short.[6][7] While inhaling and exhaling, the meditator practises: training the mind to be sensitive to one or more of: the entire body, rapture, pleasure, the mind itself, and mental processes training the mind to be focused on one or more of: inconstancy, dispassion, cessation, and relinquishment steadying, satisfying, or releasing the mind. A popular non-canonical method used today, loosely based on the Visuddhimagga, follows four stages: 1.counting each breath at the end of exhalation 2.counting each breath at the beginning of inhalation 3.focusing on the breath without counting 4.focusing only on the spot where the breath enters and leaves the nostrils (i.e., the nostril and upper lip area).[8] [edit] Modern sourcesFirst, for the practice to be successful, one should dedicate the practice, and set out the goal of the meditation session.[9] One may decide to either practice ānāpānasati while seated or while walking, or to alternate seated and walking meditation.[10] Then one may concentrate on the breath going through one's nose: the pressure in the nostrils on each inhalation, and the feeling of the breath moving along the upper lip on each exhalation.[10] Other times practitioners are advised to attend to the breath at the tanden, a point slightly below the navel and beneath the surface of the body.[11] Practitioners may choose to count each inhalation, "1, 2, 3,..." and so on, up to 10, and then begin from 1 again. Alternatively people sometimes count the exhalation, "1, 2, 3,...," or both the inhalation and exhalation.[11] If the count is lost then one should start again from the beginning. The type of practice recommended in The Three Pillars of Zen is for one to count "1, 2, 3,..." on the inhalation for a while, then to eventually switch to counting on the exhalation, then eventually, once one has more consistent success in keeping track of the count, to begin to pay attention to the breath without counting. There are practitioners who only count the breath all their lives as well.[12] Beginning students are often advised to keep their practice short, around 10 or 15 minutes a day. Also, a teacher or guide of some sort is often considered to be essential in Buddhist practice, as well as the sangha for support. When one becomes distracted from the breath, which happens to both beginning and adept practitioners, either by a thought or something else, then one simply returns their attention back to the breath. Philippe Goldin has said that important, "learning," occurs at the moment when practitioners turn their attention back to the object of focus, the breath.[13] [edit] Active breathing, passive breathingSee also: Pranayama Anapanasati is most commonly practiced with attention centered on the breath, while breathing let done naturally. One exception to this is the bamboo method, during which time one will inhale in short gasps and then exhale in short gasps, as if running one's hand along the stalk of a bamboo tree.[12] In the throat singing prevalent amongst the Buddhist monks of Tibet and Mongolia[14] the long and slow outbreath during chanting is the core of the practice. The sound of the chant also serves to focus the mind in one-pointed concentration samadhi, while the sense of self dissolves as awareness becomes absorbed into a realm of pure sound. In Zen meditation, the emphasis is upon maintaining "strength in the abdominal area" [15] (dantian or "tanden") and slow deep breathing during the long outbreath, again to assist the attainment of a mental state of one-pointed concentration. [edit] BenefitsIt has been scientifically demonstrated that practicing ānāpānasati improves one's ability to focus, improves executive functioning, slows down the natural aging process of the brain, and both increases and maintains the amount of grey matter in the brain in regions involved with watching the breath. See also Research on meditation. [edit] Stages of ĀnāpānasatiFormally, there are sixteen stages — or contemplations — of ānāpānasati. These are divided into four tetrads (i.e., sets or groups of four). The first four steps involve focusing the mind on breathing, which is the 'body-conditioner' (Pali: kāya-sankhāra). The second tetrad involves focusing on the feelings (vedanā), which are the 'mind-conditioner' (Pali: citta-sankhāra). The third tetrad involves focusing on the mind itself (Pali: citta), and the fourth on 'mental qualities' (Pali: dhamma). (Compare right mindfulness and satipatthana.) Any ānāpānasati meditation session should progress through the stages in order, beginning at the first, whether the practitioner has performed all stages in a previous session or not. In the Chinese tradition Buddhacinga, a monk who came to China and widely propagated ānāpānasmṛti methods.In the 2nd century CE, the Buddhist monk An Shigao came from Northwest India to China and became one of the first translators of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese. He translated a version of the Ānāpānasmṛti Sūtra between 148 CE and 170 CE. This version is a significantly longer text than what appears in the Ekottara Āgama, and is entitled, "The Great Ānāpānasmṛti Sūtra" (Ch. 大安般守意經) (Taishō Tripiṭaka 602). At a later date, Buddhacinga, more commonly known as Fotudeng (佛圖澄) (231-349 CE), came from Central Asia to China in 310 CE and propagated Buddhism widely. He is said to have demonstrated many spiritual powers, and was able to convert the warlords in this region of China over to Buddhism.[16] He is especially known for teaching methods of meditation, and especially ānāpānasmṛti. Fotudeng widely taught ānāpānasmṛti through methods of counting breaths, so as to temper to the breathing, simultaneously focusing the mind into a state of peaceful meditative concentration.[17] By teaching meditation methods as well as doctrine, Fotudeng popularized Buddhism quickly. According to Nan Huaijin, "Besides all its theoretical accounts of emptiness and existence, Buddhism also offered methods for genuine realization of spiritual powers and meditative concentration that could be relied upon. This is the reason that Buddhism began to develop so vigorously in China with Fotudeng."[17]  Buddhacinga, a monk who came to China and widely propagated ānāpānasmṛti methods. Buddhacinga, a monk who came to China and widely propagated ānāpānasmṛti methods.As more monks such as Kumārajīva, Dharmanandi, Gautama Saṃghadeva, and Buddhabhadra came to the East, translations of meditation texts did as well, which often taught various methods of ānāpānasmṛti that were being used in India. These became integrated in various Buddhist traditions, as well as into non-Buddhist traditions such as Daoism. In the 6th century CE, the Tiantai school was formed, teaching the One Vehicle (Skt. Ekayāna), the vehicle of attaining Buddhahood, as the main principle, and three forms of śamatha-vipaśyanā correlated with the meditative perspectives of emptiness, provisional existence, and the mean, as the method of cultivating realization.[18] The Tiantai school places emphasis on ānāpānasmṛti in accordance with the principles of śamatha and vipaśyanā. In China, the Tiantai understanding of meditation has had the reputation of being the most systematic and comprehensive of all.[19] The founder of the Tiantai school, Śramaṇa Zhiyi, wrote many commentaries and treatises on meditation. Of these texts, Zhiyi's Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā (Ch. 小止観), his Mahā-śamatha-vipaśyanā (Ch. 摩訶止観), and his Six Subtle Dharma Gates (Ch. 六妙法門) are the most widely read in China.[19] Zhiyi classifies breathing into four main categories: panting (喘), unhurried breathing (風), deep and quiet breathing (氣), and stillness or rest (息). Zhiyi holds that the first three kinds of breathing are incorrect, while the fourth is correct, and that the breathing should reach stillness and rest.[20] Venerable Hsuan Hua, who taught Chán/Zen and Pure Land Buddhism, also taught that the external breathing reaches a state of stillness in correct meditation:[21] A practitioner with sufficient skill does not breathe externally. That external breathing has stopped, but the internal breathing functions. With internal breathing there is no exhalation through the nose or mouth, but all pores on the body are breathing. A person who is breathing internally appears to be dead, but actually he has not died. He does not breathe externally, but the internal breathing has come alive. [edit] In the Tibetan traditionTwo of the most important Mahāyāna philosophers, Asaṅga and Vasubandhu, in the Śrāvakabhūmi chapter of the Yogācārabhūmi-śāstra and the Abhidharma-kośa, respectively, make it clear that they consider ānāpānasmṛti a profound practice leading to vipaśyanā (in accordance with the teachings of the Buddha in the Sutra pitika).[22] However, as scholar Leah Zahler has demonstrated, "the practice traditions related to Vasubandhu's or Asaṅga's presentations of breath meditation were probably not transmitted to Tibet."[23] Asaṅga correlates the sixteen stages ānāpānasmṛti with the four smṛtyupasthānas in the same way that the Ānāpānasmṛti Sutra does, but because he does not make this explicit the point was lost on later Tibetan commentators.[24] As a result, the largest Tibetan lineage, the Geluk, came to view ānāpānasmṛti as a mere preparatory practice useful for settling the mind but nothing more.[25] Zahler writes: The practice tradition suggested by the Treasury itself--and also by Asaṅga's Grounds of Hearers--is one in which mindfulness of breathing becomes a basis for inductive reasoning on such topics as the five aggregates; as a result of such inductive reasoning, the meditator progresses through the Hearer paths of preparation, seeing, and meditation. It seems at least possible that both Vasubandhu and Asaṅga presented their respective versions of such a method, analogous to but different from modern Theravāda insight meditation, and that Gelukpa scholars were unable to reconstruct it in the absence of a practice tradition because of the great difference between this type of inductive meditative reasoning based on observation and the types of meditative reasoning using consequences (thal 'gyur, prasaanga) or syllogisms (sbyor ba, prayoga) with which Gelukpas were familiar. Thus, although Gelukpa scholars give detailed intepretations of the systems of breath meditation set forth in Vasubandu's and Asaṅga's texts, they may not fully account for the higher stages of breath meditation set forth in those texts. . . it appears that neither the Gelukpa texbook writers nor modern scholars such as Lati Rinpoche and Gendun Lodro were in a position to conclude that the first moment of the fifth stage of Vasubandhu's system of breath meditation coincides with the attainment of special insight and that, therefore, the first four stages must be a method for cultivating special insight [although this is clearly the case].[26] Zahler continues, "it appears . .that a meditative tradition consisting of analysis based on observation—inductive reasoning within meditation—was not transmitted to Tibet; what Gelukpa writers call analytical meditation is syllogistic reasoning within meditation. Thus, Jamyang Shaypa fails to recognize the possibility of an 'analytical meditation' based on observation, even when he cites passages on breath meditation from Vasubandhu's Treasury of Manifest Knowledge and, especially, Asaṅga's Grounds of Hearers that appear to describe it."[27] Stephen Batchelor, who for years was monk in the Gelukpa lineage, experienced this firsthand. He writes, "such systematic practice of mindfulness was not preserved in the Tibetan traditions. The Gelugpa lamas know about such methods and can point to long descriptions of mindfulness in their Abhidharma works, but the living application of the practice has largely been lost. (Only in dzog-chen, with the idea of 'awareness' [rig pa] do we find something similar.) For many Tibetans the very term 'mindfulness' (sati in Pali, rendered in Tibetan by dran pa) has come to be understood almost exclusively as 'memory' or 'recollection.'"[28] As Batchelor noted, however, in other traditions, particularly the Kagyu and Nyingma, mindfulness based on ānāpānasmṛti practice is considered to be quite profound, particularly as an integral component of the practices of Mahāmudrā and Dzogchen, respectively. For the Kagyupa, in the context of mahāmudrā, ānāpānasmṛti is thought to be the ideal way for the meditator to transition into taking the mind itself as the object of meditation and generating vipaśyanā on that basis.[29] The prominent contemporary Kagyu/Nyingma master Chogyam Trungpa, echoing the Kagyu Mahāmudrā view, wrote, "your breathing is the closest you can come to a picture of your mind. It is the portrait of your mind in some sense. . .The traditional recommendation in the lineage of meditators that developed in the Kagyu-Nyingma tradition is based on the idea of mixing mind and breath."[30] Although the Gelukpa allow that it is possible to take the mind itself as the object of meditation, they traditionally discourage it with "what seem to be thinly disguised sectarian polemics against the Nyingma Great Completeness [Dzogchen] and Kagyu Great Seal [mahāmudrā] meditations."[31] Trungpa made the group practice of ānāpānasmṛti a cornerstone of his teaching in the West, although this is almost unheard of in the Tibetan tradition, where some form of visualization, syllogistic reasoning, or virtuous quality is the typical meditation object of choice (outside of the context of Mahāmudrā) and group practice invariably comprises chanting and ritual. In the Pañcakrama tantric tradition ascribed to (the Vajrayana) Nagarjuna, ānāpānasmṛti counting breaths is said to be sufficient to provoke an experience of vipaśyanā (although it occurs in the context of "formal tantric practice of the completion stage in highest yogatantra").[32][33] [edit] Notes1.^ In the Pali canon, the instructions for anapanasati are presented as either one tetrad (four instructions) or four tetrads (16 instructions). The most famous exposition of four tetrads — after which Theravada countries have a national holiday (see uposatha) — is the Anapanasati Sutta, found in the Majjhima Nikaya (MN), sutta number 118 (for instance, see Thanissaro, 2006). Other discourses which describe the full four tetrads can be found in the Samyutta Nikaya's Anapana-samyutta (Ch. 54), such as SN 54.6 (Thanissaro, 2006a), SN 54.8 (Thanissaro, 2006b) and SN 54.13 (Thanissaro, 1995a). The one-tetrad exposition of anapanasati is found, for instance, in the Kayagata-sati Sutta (MN 119; Thanissaro, 1997), the Maha-satipatthana Sutta (DN 22; Thanissaro, 2000) and the Satipatthana Sutta (MN 10; Thanissaro, 1995b). 2.^ In regards to practicing anapanasati in tandem with other frames of reference (satipatthana), Thanissaro (2000) writes: At first glance, the four frames of reference for satipatthana practice sound like four different meditation exercises, but MN 118 [the Anapanasati Sutta] makes clear that they can all center on a single practice: keeping the breath in mind. When the mind is with the breath, all four frames of reference are right there. The difference lies simply in the subtlety of one's focus.... s a meditator get more skilled in staying with the breath, the practice of satipatthana gives greater sensitivity in peeling away ever more subtle layers of participation in the present moment until nothing is left standing in the way of total release.

3.^ According to Kamalashila (2004), one practices anapanasati with mettā bhāvanā in order to prevent withdrawal from the world and the loss of compassion.

4.^ Anālayo (2006), p. 125.

5.^ "A Sketch of the Buddha's Life". Access to Insight. www.accesstoinsight.org/ptf/buddha.html. Retrieved 2007-12-03. 6.^ Majjhima Nikaya, Sutta No. 118, Section No. 2, translated from the Pali 7.^ Satipatthana Sutta 8.^ Kamalashila (2004). Meditation: The Buddhist Way of Tranquillity and Insight. Birmingham: Windhorse Publications; 2r.e. edition. ISBN 1-899579-05-2. . Regarding this list's items, the use of counting methods is not found in the Pali Canon and is attributed to the Buddhaghosa in his Visuddhimagga. According to the Visuddhimagga, counting (Pali: gaṇanā) is a preliminary technique, sensitizing one to the breath's arising and ceasing, to be abandoned once one has consistent mindful connection (anubandhā) with in- and out-breaths (Vsm VIII, 195-196). Sustained breath-counting can be soporific or cause thought proliferation (see, e.g., Anālayo, 2006, p. 133, n. 68). 9.^ John Dunne talks on Buddhist phenomenology from the Indo-Tibetan textual point of view at ccare.stanford.edu/node/2110.^ a b The Three Pillars of Zen 11.^ a b "The Three Pillars of Zen" edited by Philip Kapleau 12.^ a b "Zen Training: Methods and Philosophy" by Katsuki Sekida 13.^ Philippe Goldin in Cognitive Neuroscience of Mindfulness Meditation www.youtube.com/watch?v=sf6Q0G1iHBI14.^ The One Voice Chord 15.^ Tanden: Source of Spiritual Strength 16.^ Nan, Huai-Chin. Basic Buddhism: Exploring Buddhism and Zen. 1997. pp. 80-81 17.^ a b Nan, Huai-Chin. Basic Buddhism: Exploring Buddhism and Zen. 1997. p. 81 18.^ Nan, Huai-Chin. Basic Buddhism: Exploring Buddhism and Zen. 1997. p. 91 19.^ a b Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 110 20.^ Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation. 1964. p. 125 21.^ Hsuan Hua. The Chan Handbook. 2004. p. 44 22.^ Study and Practice of Meditation: Tibetan Interpretations of the Concentrations and Formless Absorptions by Leah Zahler. Snow Lion Publications: 2009 pg 107-108) 23.^ Study and Practice of Meditation: Tibetan Interpretations of the Concentrations and Formless Absorptions by Leah Zahler. Snow Lion Publications: 2009 pg 108) 24.^ Zahler 119-126 25.^ Zahler 108 26.^ Zahler 108, 113 27.^ Zahler 306 28.^ The Faith to Doubt: Glimpses of Buddhist Uncertainty. by Stephen Batchelor. Parallax Press Berkeley: 1990 pg 8 29.^ Pointing Out the Great Way: The Stages of Meditation in the Mahamudra tradition by Dan Brown. Wisdom Publications: 2006 pg 221-34 30.^ The Path is the Goal, in The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa, Vol Two. Shambhala Publications. pgs 49, 51 31.^ (Zahler 131-2) 32.^ Pointing Out the Great Way: The Stages of Meditation in the Mahamudra tradition by Dan Brown. Wisdom Publications: 2006 pg 221 33.^ A Direct Path to the Buddha Within: Go Lotsawa's Mahamudra Interpretation of the Ratnagotra-Vighaga. by Klaus-Dieter Mathes, Wisdom Publications 2008 pg 378

|

|

|

|

Post by TCTV on Dec 27, 2010 16:49:30 GMT -5